Therapeutic Guidelines when resources are limited

Written for ISIUM by Rob Moulds

There are two basic reasons why Guidelines making recommendations about patient care are usually written:

There are two basic reasons why Guidelines making recommendations about patient care are usually written:

- The first is that there is a perceived (or real) problem that the care of patients in particular circumstances is thought to be deficient and/or requiring change. So the guidelines aim to bring about changes in practice.

- The second is that healthcare practitioners find themselves in clinical situations in which they are uncertain as to the best course of action and are actively seeking assistance. So the guidelines are written to meet this need.

Of course these two reasons are not mutually exclusive, but usually one or the other predominates.

Before ever considering writing guidelines, it is important to recognise these different purposes for guidelines because they usually result in quite different types of guidelines.

Guidelines primarily intended to change practice

These types of guidelines are the types of ‘formal’, or ‘reference’, guidelines that usually have the following characteristics:

- They are often instigated and published by governments and/or professional organisations because of a perceived deficiency in care

- If initiated by government it is often because the usual care being provided is thought to be more expensive than necessary and equally effective, but cheaper, care needs to be encouraged

- If initiated by a professional organisation it is often because members of the professional organisation do not consider that the usual care being provided by other practitioners is ‘best practice’.

- They have a formal structure which includes a comprehensive review of all the available evidence relevant to the proposed guideline, and then grading of recommendations based on the robustness of the evidence and the clinical importance of the recommendation as judged by appropriate clinical specialists.

- They are usually overseen by a group of senior clinical experts, but most of the research and writing of the guidelines is undertaken by project officers/managers or similar staff whose expertise is in information management and evidence review rather than clinical medicine.

- In order to incorporate the evidence and the grading of its robustness and importance, they are usually lengthy and densely written, and not easily readable by busy practitioners.

- Because of the way they are produced, they usually take a long time to write and require considerable resources

- They are universal – in the sense that ideal, evidence based management of a specific clinical problem should not vary between healthcare systems and/or be limited by inadequate resources.

Because of the above characteristics these types of guidelines have significant strengths, but they also have significant weaknesses.

Their major strength is that they are usually robust and trustworthy, and users can be confident any specific recommendations made will be based on sound evidence. They therefore usually provide a sound basis for important decisions that might be required to implement their recommendations, for example the provision of an expensive new drug or investigation, or changes in a healthcare practice such as increased referral of patients with a particular condition to more highly trained practitioners.

Their major weaknesses are first, because of their comprehensive nature and the way they are written, they are usually very expensive and time consuming to write – so funding is usually a major issue. Second, they are not good at making recommendations for complex situations where there is a lack of evidence – for example patients with multiple comorbidities – and often simply state there is a lack of evidence, or don’t even address the situation at all. Third – and probably their biggest weakness – is that many studies have shown that the writing and promulgation of such types of guidelines seldom results in changes to practice. Changes only occur if the guidelines are incorporated into comprehensive educational activities or result in regulatory changes or structural changes within the healthcare system.

The reasons why these types of guidelines tend not to be followed by practitioners unless they are accompanied by some sort of incentive, or even compulsion, are not so well understood. However likely important factors are that current practices are often entrenched for reasons that are not addressed by the guidelines, and also there is often a lack of trust by practitioners that ulterior motives have not in some way influenced their content – for example to save money if they have been initiated by government, or to advance their own professional interests if initiated by a professional organisation.

Guidelines primarily intended to assist practitioners faced with difficult clinical situations

These types of guidelines are often referred to as ‘point of care’ guidelines and usually have the following characteristics:

- They are succinct and, although based as much as practicable on sound evidence, usually they don’t overtly give a full evidence base for many of their recommendations.

- Because they are written with the aim that they can easily be referred to at the actual time of decision making, they pay very close attention to ease of access to the guidelines and mode of presentation of their recommendations.

- Because the situations where practitioners are seeking assistance are often the very situations for which there is little or no evidence to guide them, the guidelines are of necessity often based on expert opinion rather than robust evidence.

- They are usually contextualised as much as possible to take into account the differing circumstances in which practitioners are likely to be placed when making clinical decisions.

- They vary considerably in their complexity and types of recommendations depending on the scope of practice of the practitioners they aim to assist.

As with the more formal types of guidelines, these types also have strengths and weaknesses. Their major strength is that because they are primarily written to help practitioners and particularly focus on ease of access and the clarity and practical relevance of their recommendations, they are likely to be valued, and their recommendations are likely to be followed, by practitioners. This has the added benefit that some form of user-pay funding by either the practitioner or their employer might be practical, so their funding can be less problematic than the first type of guideline. In order to ensure their practical relevance, the writers are also often clinicians themselves and are often prepared to provide their services and expertise for little or no recompense in the spirit of helping their fellow practitioners.

Their major weakness is that recommendations made in the absence of robust evidence are inevitably open to challenge, for example by a pharmaceutical company whose product is not recommended as first-line treatment in certain circumstances, or by practitioners who perform a particular procedure about which the guidelines express reservations. A second significant weakness is that users must have a high degree of trust that the writers have the appropriate experience and expertise to be able to give clinical advice that can be confidently followed, and also that the writers themselves do not have conflicts of interest, either declared or undeclared, which could influence their recommendations.

Which way to go?

It is clear from the above that whenever plans are being made to write, publish and promulgate guidelines, the first and most important question that must be addressed is what the primary purpose of the guidelines is.

If the primary purpose is to change practice, further questions that must then be addressed include:

- Recognising that these types of guidelines are in a sense ‘universal’, what other reputable guidelines are available around the world relating to the particular questions being addressed by the proposed guidelines?

- Whilst recognising that there is no point in reinventing wheels, but also that no process is infallible, how necessary is it to replicate the evidence searches and analyses that might have been undertaken by others?

- Notwithstanding the above, if other guidelines are to be used, what will be the extent of the changes that will need to be incorporated to take into account local constraints that could make it impossible to implement ‘ideal’ practice, either in the short term or in the long term?

- Depending on the answer to the above question, what will be the process required to make those changes?

- Who are the key local opinion leaders and organisations whose agreement on the appropriateness of the guidelines will be required, and how much input from them will be required for them to be comfortable in giving their agreement?

- Recognising that these types of guidelines alone are unlikely to result in changes in practice, what form of educational activities and/or regulatory changes will be required to accompany them, and what might be the impediments to the implementation of those activities or changes?

If the primary purpose is to assist practitioners in their everyday activities, further questions that must then be addressed are:

- What is the scope of practice of those practitioners, and what are the particular problems they face in their practice?

- How will the practitioners access the guidelines when they need them?

- What format will best enable the practitioners to easily find the relevant advice they are seeking?

- Recognising that all ‘point of care’ guidelines need contextualising to local circumstances, what sorts of similar guidelines are available elsewhere that might at least provide a template for adaptation?

- If guidelines are to be written locally, who will be responsible for writing them? If guidelines from elsewhere are to be adapted, who will be responsible for the adaptation?

- Who are the key opinion leaders whose agreement to the recommendations and advice contained in the guidelines will be required?

- How will input from the proposed end users be obtained to ensure the guidelines really are addressing their problems and making practical recommendations?

It is, of course, usually much easier to ask these questions than to answer them. Some questions are also common to both types of guidelines, for example how best to involve key opinion leaders and organisations, but the answers to those questions will likely differ depending on the type of guideline decided upon.

The effect of limited resources

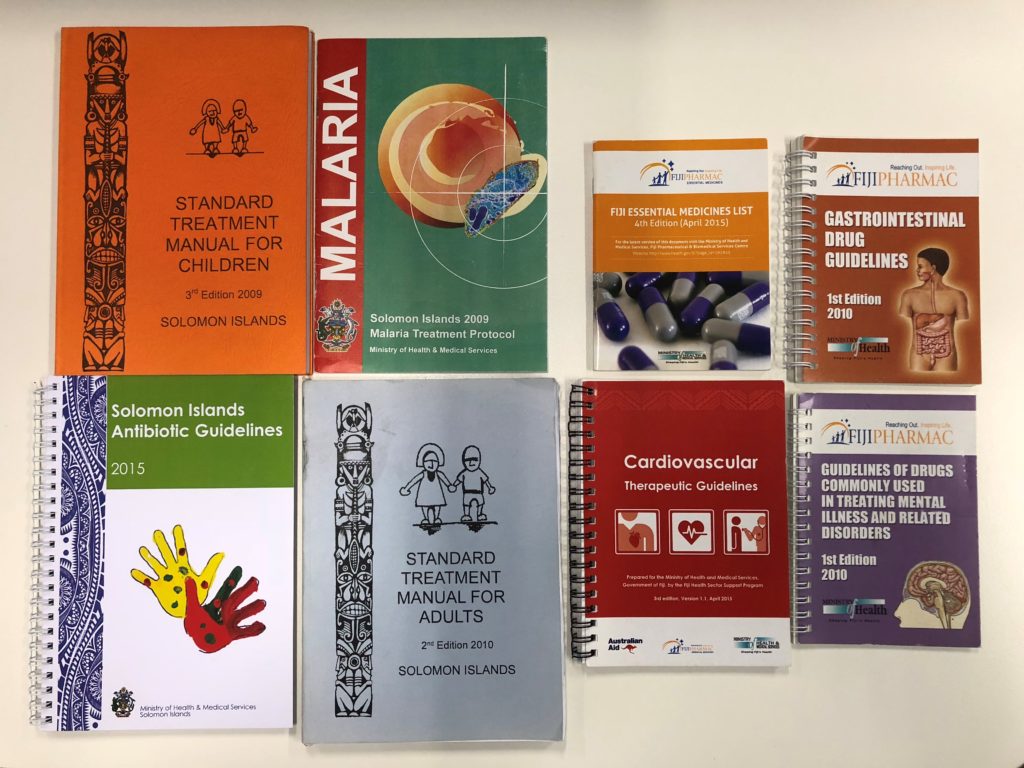

The major resources required to write guidelines are financial (ie having enough money to pay for the people involved and the publication and promulgation of the guidelines) and human (i.e. having people available with the appropriate clinical and publishing expertise). Countries all vary in their access to resources, but some generalisations can probably be made between a resource rich environment, such as Australia, and an environment where overall resources are much more limited, such as a small Pacific Island country.

1) The major resource limitation in a country like Australia is likely to be financial – for example the expertise is available but who is going to pay for them? The major resource limitation in a small Pacific Island country is likely to be human – for example funding has been made available but who has the expertise to write the guideline?

1) The major resource limitation in a country like Australia is likely to be financial – for example the expertise is available but who is going to pay for them? The major resource limitation in a small Pacific Island country is likely to be human – for example funding has been made available but who has the expertise to write the guideline?

2) Whenever there are financial resource limitations, conflicts of interest will inevitably arise which must be recognised and managed transparently if the guidelines are to achieve their purpose.

3) Conflicts of interest are likely to be different in different situations, and not always an obvious conflict such as direct funding from a pharmaceutical company. A rule of thumb should be that all sources of funding will somehow have ‘strings’ attached which need to be clearly understood in order for them to be appropriately managed.

4) Human resource limitations will usually make it impossible for a small country to even contemplate writing ‘practice changing’, or ‘reference’, types of guidelines.

5) Small countries will also often have difficulty finding people with the time and expertise to modify existing guidelines. Suitable expats might be available, for example recent retirees, but ‘backfilling’ of current clinical responsibilities of local clinicians might be required to free up those clinicians for the required time.

Summary

Guidelines come in many shapes and sizes, and their writing can serve many different purposes. If the writing of a particular guideline is to achieve its aims, it is essential that all contributors understand the purpose of the guideline and the method of its writing is appropriate for the intended purpose. Coping with resource limitations will be an essential feature of most guideline writing, but the limitations will likely be different in different circumstances.